In light of the disappointing way price responded to the extraordinary monetary response from the world’s central banks, it is worth considering the limitations of policy. In a metaphorical sense, the Fed’s actions while necessary and welcome, were like bringing a knife to a gun fight. The Fed’s actions obviously lowered the risk free cost of capital to zero. It also initiated a $700 billion asset purchase program and eliminated the bank reserve requirement. These measures will hopefully ensure an ample degree of liquidity in the banking system. However, a plausible reason why price responded poorly was that the crisis is not a problem of liquidity in the banking sector, but due to the availability of cash flow and credit to the corporate sector, small business and some households.

The key limitation of the existing measures is that under the current laws, the Fed cannot purchase corporate debt or commercial paper. The Federal Reserve Act lays out the securities that the Fed can buy. Corporations are not included. As UBS noted, the same prohibition existed in the 2008 financial crisis and the Fed did not purchase corporate debt. Congress could change the Federal Reserve Act, but that would require legislation. On the positive side, Congress could easily appropriate funds for the Treasury Department to purchase corporate debt. Another possible action might involve the Fed lending to a broad basket of corporate paper or debt issuers, but it would have to be done in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and it would have to be collateralised. Non-financial borrowers would also likely have difficulty finding collateral (which would also have to have a haircut).

Moreover, it would still be difficult to ask lenders to turn a blind eye to credit risk, particularly given the underlying macro conditions. Another way to address the issue would be for the administration to provide a range of loan guarantees similar to the United Kingdom. A facility does exist under the small business administration, but this facility would likely need to be increased materially from current levels – the President has already indicated that this should be increased to $90 billion. Even more cash flow and guarantees would likely be required. Fiscal policy support more broadly probably needs to be considerably larger given the potential loss of aggregate demand. New Zealand announced a 4% of GDP package this morning. That is likely closer to the required amount and similar to China’s response (as a proportion of GDP) in 2008. For the United States, that implies a fiscal package well north of $1 trillion.

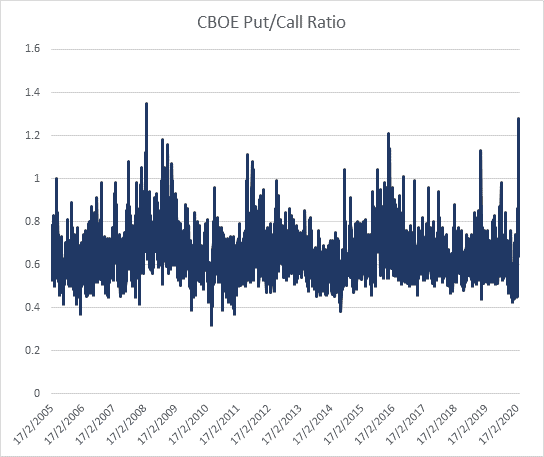

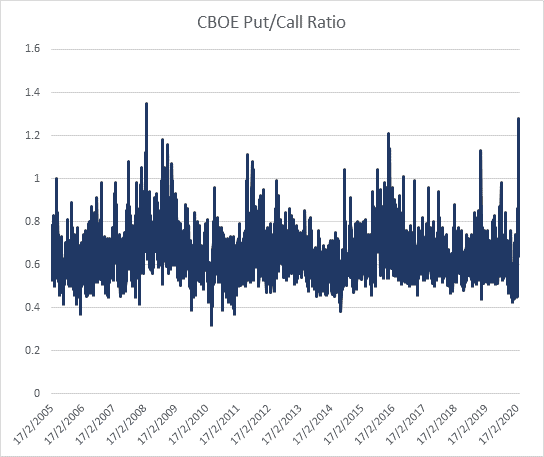

For markets, the good news is that a range of sentiment and valuation indicators are near extreme levels. The put/call ratio and market skew is similar to the levels at the depths of the crisis in 2008 (chart 1). A range of other sentiment and positioning indicators show similar extremes. From a fundamental perspective, the spread of the earnings yield relative to Treasury yield is also near the relative extreme in 2008/9 and 2011/12 (chart 2). Of course, the conditional element of valuation – the earnings – are clearly likely to take a material hit. The first manufacturing survey for March, the Empire State survey, declined by the most in history and is consistent with a 2008-style collapse in growth and profits.

In conclusion, markets are approaching a tactical extreme. Policy is moving rapidly in the right direction, although needs to have a greater focus on cash flow support and guarantees for the corporate sector. Of course, the healthcare policy response of containment has also contributed to the economic contraction. Markets will also likely need to see a peak in new cases in the West.